Remittances and Our Freedom to Give

A crucial alternative to foreign aid is being threatened.

Remittances, the funds immigrants send to family members in their countries of origin, are under political fire. Many US policymakers favor taxing these payments and placing bureaucratic hurdles in the way of those trying to send money home. The rationale? Keep more money circulating in the US economy. It’s a seductive argument for many. Yet this idea is not only shortsighted but harmful.

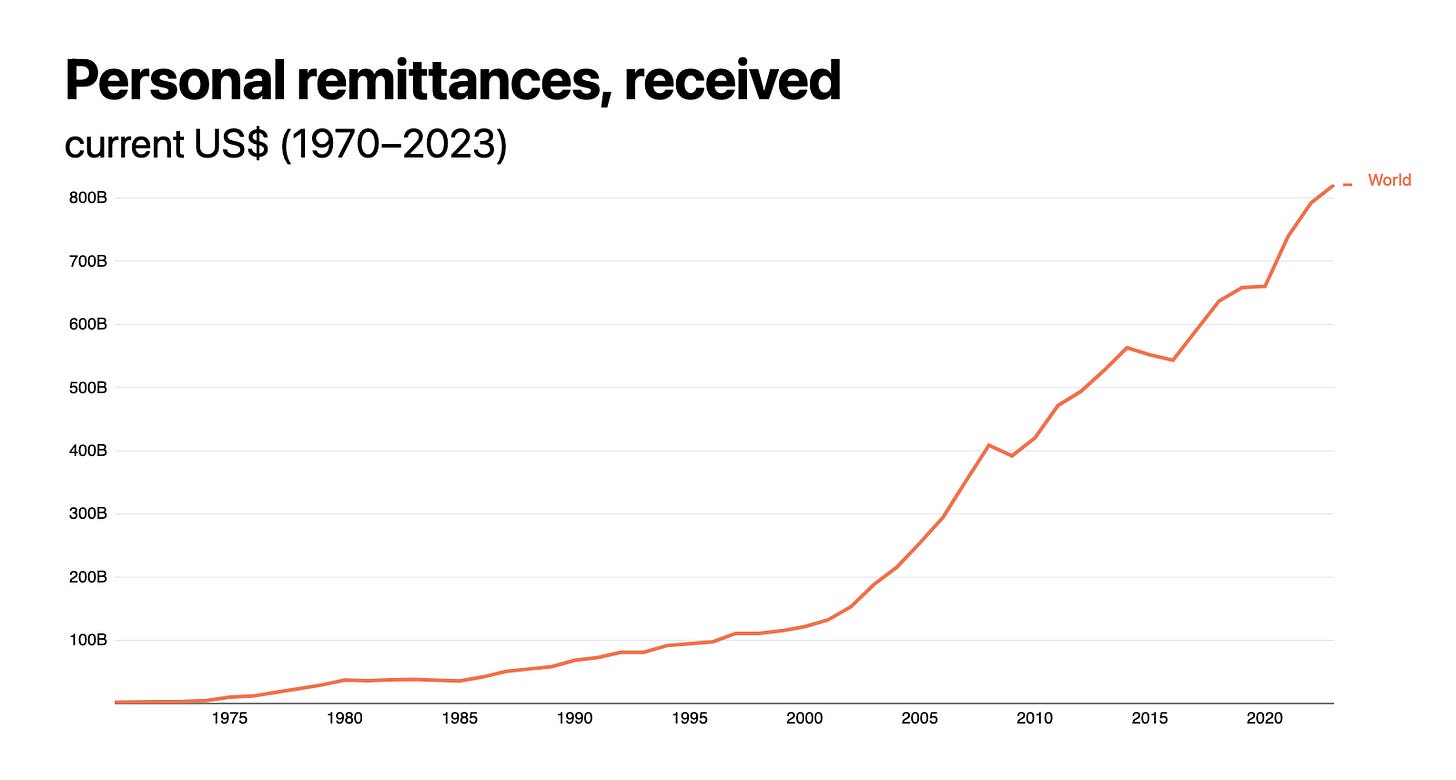

First, consider the scale of these payments. The average global migrant worker sends 15 percent of their salary back home. That is only about $250 every 1 to 2 months, but it represents one-half the average monthly salary after tax of a worker in El Salvador, and just above the average monthly salary of a worker in Bangladesh. Thus, the flow of cash from a migrant worker can determine who back home can afford a metal roof, a well, pavement, nutritious food, payment of debt, medical coverage, or education.

The United Nations estimates that one billion people worldwide either pay or receive remittances. The World Bank anticipates that global remittance payments sent to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) will total $690 billion by the end of 2025. The amount of money sent by migrants more than tripled global foreign aid money in 2021.

Unlike foreign aid, remittances don’t cost US taxpayers a dime. According to Robert Stojanov and Wadim Strielkowski, remittances are absorbed nearly twice as effectively as official development assistance, or foreign aid for development. The absorption rate represents how effectively money is used and traded in the economy it enters. In other words, money given by remittances is often more effectively used in local developing economies than money provided through foreign aid.

Remittances are especially important for families because they can reduce child mortality and child labor. When parents receive steady financial support from family members abroad, they are better able to support their children and afford medical care for them. The children, in turn, are less burdened by the need to work and can attend school.

Remittances are also crucial in times of economic uncertainty. During the COVID-19 pandemic, remittances accounted for more than 30 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) for The Gambia and Lebanon, providing essential support for recipients and boosting local economic activity.

In the early 2010s, internet and mobile phone access were still limited in many developing countries. However, in just the past decade, the world has seen a 30 percent increase in internet users worldwide, and the World Bank estimates that 84 percent of people in developing countries own a mobile phone in 2025. Importantly, the adoption of mobile phones correlates with the adoption of mobile money accounts, facilitating millions of remittances.

Western Union is the dominant remittance handler in the developing world and has historically used its comfortable market share to impose high fees to transfer remittances. However, because of the spread of mobile devices in the developing world, fintech companies such as Wise and Remitly have since entered the remittance market, offering users lower transfer fees and forcing Western Union to lower its fees in turn.

Prior to the information age, most of Africa suffered from a lack of financial infrastructure, such as automated teller machines (ATM), banks, and tellers. However, since the distribution of mobile devices, companies such as Wave and M-PESA have experienced strong adoption of mobile remittance transfers. These mobile money payments, like those traditionally handled by Western Union, reduce poverty and income inequality in developing countries, but with much lower transfer costs and infrastructure needs.

Remittances also represent an essential human freedom: the right to give. Just as Americans can freely send money through Venmo and Zelle without government interference, individuals who transfer funds internationally should enjoy the same freedom. However, the recently passed One Big Beautiful Bill Act will put a 1 percent excise tax on remittances.

A world with greater freedom and improved economic development demands that all people are free to send and receive money. As calculated by the Center for Global Development, “for many low- and middle-income countries, the impact of the remittance tax far outweighs the impact of known US aid cuts conducted so far.”

During an interview with me, Helen Dempster of the Center for Global Development stated that a remittance tax could decrease remittances themselves. This decrease in transfers may incentivize banks and lenders to charge higher fees. According to Dempster in the interview on July 4th, 2025:

There’s been a campaign for 20 years now to reduce the cost of sending remittances and many remittance service providers, particularly the large ones like Western Union, are keeping fees stubbornly high. I think if they wanted to keep fees low to encourage remittances, they would have reduced their fees by now. So, my sense is that they will pass the whole amount of the cost on to consumers.

Because of this tax, some of the most powerless individuals will suffer the cost, and the US will earn negligible revenue. As we’ve seen in past decades, greater freedom to migrants and competition between lenders directly improve the lives of the global poor. Ultimately, preserving our freedom to give not only protects our human rights, but positively transforms the day-to-day lives of millions and the future of the developing world.

Author: Camille Miner, a student at UC Berkeley studying Philosophy and Social Welfare and a former Research Intern at Human Progress.

"Unlike foreign aid, remittances don’t cost US taxpayers a dime."

I'm going to have to call BS on that one. You are looking only at taxes collected for foreign aid, and not the economic impact of immigrants being here and making money here.

The vast majority of remittances come from illegal aliens who are working under the table, not paying taxes, and taking jobs from and lowering wages for American workers. These illegals are simultaneous collecting welfare, using Medicaid, sending their kids to public schools, crowding our ERs for minor ailments because they refuse to get a primary care doctor, getting food stamps (yes, I know it's a card now), getting WIC, living in public housing (or being put up in hotels at taxpayer expense), often being given cash payments, voting in our elections, popping out anchor babies, and probably doing other things I have no idea about. Their remittances are costing US taxpayers a almost unfathomable amount.

But I do agree that the money they send back is more effective than anything government does. Or charities either. And it is directed more appropriately. Government and charities are the most corrupt things in the world. Only a fraction of any government aid or charity money actually goes to help the people it is purported to be for.

I would much rather end all foreign aid and not tax remittances, or anything else. But at the same time we should end ALL social programs. Let those who want to work hard and/or smart and make a better life do what they want with their money, immigrant or not. For those who want to sponge off the system and our charitable natures and not contribute, they can starve or leave or change their ways. Immigrant or not.

Oh if the world was so simple as we try to make it! I enjoy your articles for the alternative ways of life and they are a great respite from the regular " news". Unfortunately you seem to give human nature more credit than it deserves.

Humans are broken and broken things cannot fix broken things.There is only one true answer to our problems and yet so many reject Him.