In Trade We Trust: How Markets Build Social Fabric

Far from eroding community bonds, markets weave broader networks of trust.

In my previous piece, I argued that a trade society generates prosperity, a widespread abundance of capital. But that raises another question: Does commercial exchange also lead to an abundance of social capital? While many may accept the economic efficiency of a market economy, they may see the trade-off as the fracturing of our social fabric and the deterioration of social capital.

But trade requires trusting attitudes and trustworthy behaviors to function properly, making a commercial society equivalent to a trust-based society. The American economist Ryan Murphy of the Bridwell Institute has distinguished between what he calls bonding social capital and bridging social capital. Bonding social capital refers to what increases the bond of affection with those in our inner circle, such as our family and friends. Bridging social capital refers to what builds social bridges, expanding our social network to those outside our inner circle. Too much bonding can interfere with bridge-building and can even burn bridges, creating a host of problems such as corruption and hostility toward out-groups. Trade acts as a social bridge. And a trade society is one full of social bridges.

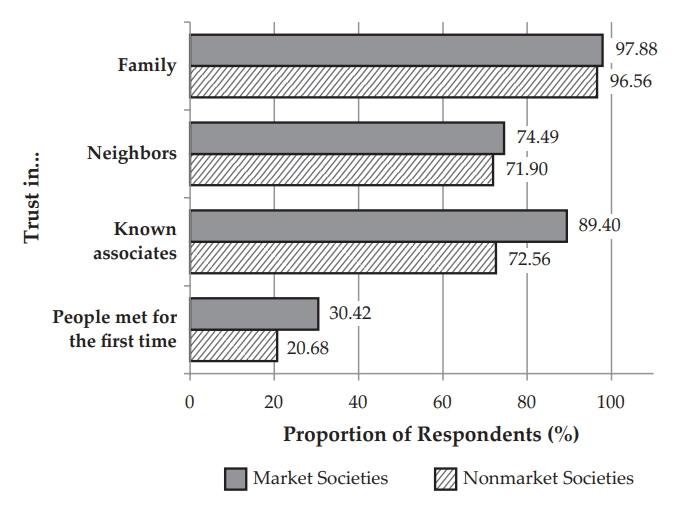

Research from the Mercatus Center’s Virgil Henry Storr and Ginny Choi demonstrates the bridge-building capacities of market economies. They found that people in both market and nonmarket societies trust close family and neighbors. However, as social distance increases—from family and friends to neighbors or strangers—trust decreases. And yet, this decline in trust is slower in market societies. Compared with those in nonmarket societies, people in market societies are more likely to (at least somewhat) trust friends, colleagues, and even strangers. As Choi and Storr concluded, “People around the world seem to have equally strong core networks, but those living in market societies seem to have stronger periphery networks.”

Figure 1. Market versus nonmarket societies on trust

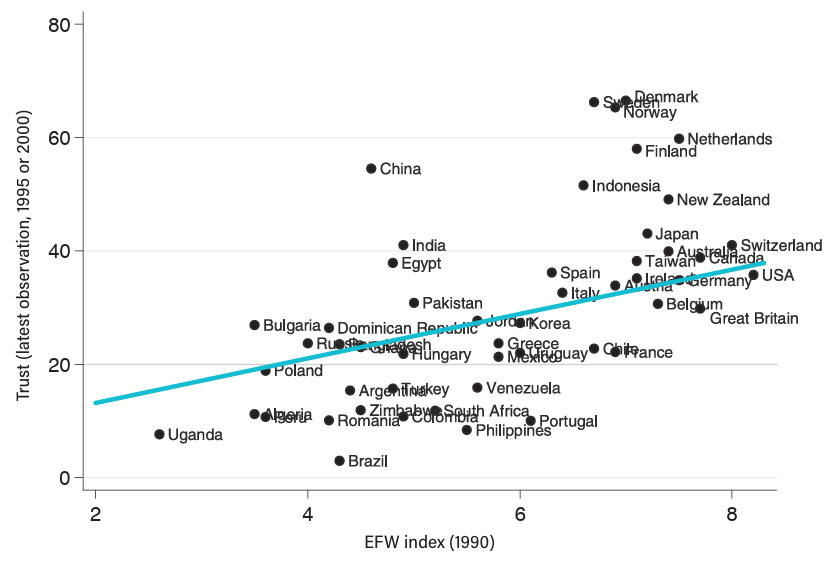

Other survey data support Storr and Choi’s findings and suggest that commercial societies produce trust. Utilizing data from the Economic Freedom of the World (EFW) index and the World Values Survey, researchers ran cross-country regressions with over 50 countries for the years 1995 and 2000. They found that economic freedom plays a significant and possibly causal role in the development of trust within countries. Even after controlling for variables such as urban population, age, human capital, government share of gross domestic product, political institutions, and inequality, countries with higher levels of economic freedom have been shown to have higher generalized trust than less free countries. But these trust levels are not fixed! Countries that experience pro-market reforms also see improvements in trust.

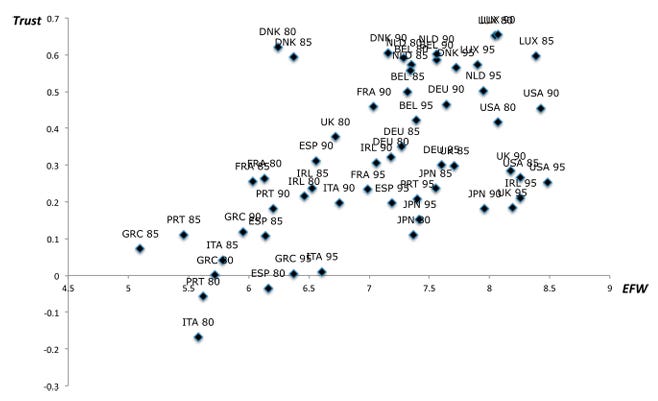

Drawing on European survey data and the EFW index, Mercer University economist Antonio Saravia looked at the effects of economic freedom on generalized trust for the years 1980, 1985, 1990, and 1995. After implementing several controls, Saravia found that a 10 percent increase in economic freedom led to a 2.5 percent increase in generalized trust.

Figure 2. Economic freedom and generalized trust across countries

Figure 3. Economic freedom and trust in Europe

The evidence appears to indicate that market-based economic institutions have a positive effect on trust. However, one of the criticisms of the trust literature is that survey data and real-world behavior do not always match up. Contrary to expectations, people tend to be more trusting and trustworthy in experiments than survey answers, and laboratory experiments can give us a better sense of how economic institutions shape the trust-based behaviors of individuals.

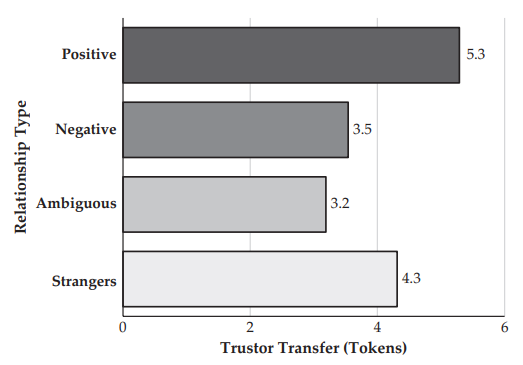

The results of various laboratory experiments by Storr and Choi are telling. In studies published between 2018 and 2022, the two researchers demonstrate that in markets where cheating is possible, participants learn to reward trustworthy partners with greater trust and reciprocity (measured through token transfers). Those with positive market interactions received significantly more tokens than cheaters. What’s more, even strangers received more tokens than cheaters. In experiments where cheating was prevented or its effect neutralized, positive relationships were treated similarly to relationships between strangers. Storr and Choi stressed that participants knew nothing about each other and could not communicate beyond offers. That means the relationships were purely commercial, with no distortions stemming from race, sex, religion, or the like. In short, when corruption and dishonesty are absent from the marketplace, trust and equal treatment emerge. When dishonesty is a factor (as it is in the real world), trustworthiness is incentivized, and dishonesty is stigmatized. Positive market transactions breed trust and trustworthiness.

Figure 4. Trustor transfers by relationship type

Using similar trust games as the one featured in Storr and Choi’s study, other laboratory experiments primed random participants to unconsciously think about markets. The results indicate that a market mindset makes people more trusting of others. George Mason University economist Omar Al-Ubaydli and colleagues explain their findings:

Priming markets leaves people more optimistic about the trustworthiness of anonymous strangers and therefore increases trusting decisions and, in turn, social efficiency. . . . Absent markets, economic interactions with strangers tend to be negative. Market proliferation allows good things to happen when interacting with strangers, thus encouraging optimism and leading to more trusting behaviors. Participation in markets, rather than making people suspicious, makes people more likely to trust anonymous strangers. Our results seem therefore to corroborate the idea of doux commerce. [Italics in original.]

Another pair of economists selected internet business professionals from two cutthroat industries: domain trading and online adult entertainment. Multiple laboratory games between these internet professionals and Berkeley students yielded surprising results: The business professionals were more trustworthy, trusting, generous, and honest. As the study’s authors put it, “Internet business people were, on the whole, ‘nicer’ than students.” An earlier study performed similar experiments with company CEOs and students. Although CEOs are often caricatured as being greedy Gordon Gekko clones, they ended up being both more trusting and more trustworthy than students in the experiments.

The fact that the commercial society exists should be awe-inspiring. The absolute scale of trust and cooperation is incredible. But markets aren’t magical. They are spaces in which people engage in repeated trade, where individuals learn to consistently rely on and cooperate with each other. As people demonstrate a pattern of trustworthy behavior, exchange becomes more fluid, and trust becomes more concrete. Long-term success in the market depends partly on developing strong bonds of trust. And this practical necessity for economic success can eventually develop into a personal virtue.

Author: Walker Wright, the manager for Academic Programs at a public policy think tank in Washington, DC, and an adjunct faculty member at Brigham Young University-Idaho. His forthcoming book, In Trade We Trust: How Commerce Makes Us More Social, will be published by Bloomsbury.

Walker Wright : This just "popped up" on my e-mail inbox !

Apposite I thought , so , here it is : https://www.prageru.com/videos/a-moral-case-for-capitalism

I hope that YOU too can find some common ground in it !

.

Regards , Trevor.

Sorry Walker Wright , but you are either incredibly gullible or naive , or both , in reaching the conclusions that you have ! I am NOT playing "Devil's advocate" here , I am just saying that your version of "human nature" is not evident anywhere in the real world or in commerce !

Trust is something that takes ages to build , but which can be destroyed in an instant !

e.g. As in many cases , the "allies" of WW1 became the "enemies" of WW11 and the "Cold War " !

e.g. Almost no business contract is done without a beneficial "sweetener" or the application of "coercion" [ e.g. wages 'negotiations'! ].

Most co-operation is achieved by coercion ![ As Mao succinctly put it : "Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun !" ] Bargaining from a position of strength ALWAYS achieves a better result for the powerful party , and it even allows them the privilege to grant concessions and 'fairness in the deal' , and even act philanthropically , if that is what they choose to do !

Very few transactions occur on a equal basis. Look no further than "mergers" and "acquisitions" in the mining industry and other industries ! One party always predominates !

If you have ever been in a retail business you would recognise that the offering of a discount or the selling of "specials" gives the purchaser the "whip hand" [ often illusory because there is a limit below which no retailer can go........unless it is defective or coercive ! ] e.g. China has blocked sales of BHP Iron Ore to Chinese Steel Mills............until they 're-negotiate' a lower price perhaps ! ??

Trade has NEVER softened a hard heart ever ....or anywhere ! China , historically , has always traded with it's neighbours , but that didn't stop them invading and conquering China ! Slaves were "freely traded" everywhere in the known world ! Not much trust elicited by trade there then !

There are just too many similar instances that prove my point , so I won't go on about it !!

The world faced by humanity has been one of constant threat , danger , poverty and misery UNTIL the WEST emerged with inventions and innovations and the Industrial Revolution ; and since then it has been a world of constant improvement in the human condition ! Apart from the outstanding Chinese invention of gun-powder , almost all inventions have come from the WEST and with it's Judeo-Christian roots and their invention and application of "science" it has produced wealth , health and prosperity on an unimaginable scale , such that poverty is almost a thing of the past !

Mastering "our world", which still does it's best to kill us , is probably "our" greatest achievement !

This was NOT attributable to trade.........conversely......it facilitated trade......because everyone now wanted what we had and what we produced ! That 'religious background' with it's ethics and morality and education produced the first glimmer of TRUST between different peoples who held the same values....even if their religion was gained from missionaries ..."down the barrel of a gun" !

No. Trust is a luxury item and it is ephemeral ....and it didn't facilitate trade then either !

I admit that trade conducted WITH TRUST will always be "better" than without it .....but nothing changes except the "warm inner glow"..........and it is still just a commercial transaction.

America is the most successful trading (and manufacturing ) country EVER . Their motto is : "In God we trust" , and it was a very Christian Country at it's founding , and the TRUST was palpable !

It is also the most generous country . Americans support many organisations financially even though the majority of those members may despise America .....they accept US money even as they mutter empty platitudes through their hypocritical teeth......like the UN !

So , the most successful country EVER , despite all it's TRADING is not trusted or even liked !

The American generosity , philanthropy , aid and protection that it has offered most of the world has back-fired dreadfully ! America is the most universally HATED country on Earth BECAUSE the recipients , instead of being grateful and appreciative , "feel" obligated and inadequate and humiliated at their need for humanitarian assistance from a more successful country !

So.......NO........TRUST and TRADE do not necessarily engender one another !