In Praise of Obsolescence: The Hidden Wealth in Products That Break

There is a tradeoff between innovation and longevity.

On a recent flight from Utah to Washington, DC, I made a new friend when I told a fellow passenger that I was going to give a presentation on how our planet was infinitely bountiful. Most people are shocked when you tell them that resources will be fine but that there are not enough people. They’ve been told all their lives that we live on a finite planet with finite resources and that if life is left “unchecked,” it will cease to exist. We had a great discussion for four hours, during which he made an important observation: Products today don’t seem like they last as long as they used to. Grandma’s refrigerator ran for 30 years, while refrigerators today seem to have a much shorter lifespan.

My fellow traveler’s point is worthy of consideration, but there’s another important factor to consider: innovation. Refrigerators that last forever miss out on the benefits of creative destruction. Harvard economist Joseph Schumpeter noted that for growth and prosperity to occur, old and inefficient products and production methods must give way to those that are new and better.

Older refrigerators often have a reputation for lasting longer, but trade-offs are at play. Pre-1990s models were built with simpler, more durable components, such as robust compressors, and could last between 20 and 30 years with minimal maintenance.

However, they were less energy efficient, consuming two to three times more electricity than modern units. Newer refrigerators, designed under stricter energy regulations (e.g., EPA’s Energy Star standards), use advanced insulation, variable-speed compressors, and eco-friendly refrigerants.

These complex systems can be prone to failures, especially in electronic controls or sensors. As such, the average lifespan for modern units is between 10 and 15 years, though high-end brands such as Sub-Zero and Bosch can match the durability of older models.

Economist Alex Tabarrok notes that

Recent research from the Association of Home Appliance Manufacturers trade group shows that in 2010 most appliances lasted from 11 to 16 years. By 2019, those numbers had dropped to a range of nine to 14 years. (In some cases, such as for gas ranges and dryers, the lifespans actually increased.)

The 15 percent decline is partially explained by government regulation. Says Tabarrok:

Every appliance service technician I spoke to—each with decades of experience repairing machines from multiple brands—immediately blamed federal regulations for water and energy efficiency for most frustrations with modern appliances . . . The main culprit is the set of efficiency standards for water and energy use for all cooking, refrigeration, and cleaning appliances.

When prices rise faster than hourly wages, the culprit is almost always government interference through excessive regulation, burdensome taxation, or inflationary policies. Unlike entrepreneurs, government officials don’t face the discipline of profit and loss. They spend without accountability and impose costs without consequences.

Entrepreneurs, by contrast, thrive by creating more with less. They compete to lower prices, improve quality, and serve more people. In the free market, profit is earned by solving problems, cutting costs, and accelerating learning. But when government breaks the feedback loop between cost and consequence, abundance begins to unravel.

Contrary to what Marxist university professors and progressive politicians claim, businesses like to lower prices, not raise them. Lower prices attract more customers, increase sales, and generate higher profits through scale. Each additional unit produced creates an opportunity to learn, improve, and reduce costs. These learning curves are the engine of progress. Lower costs enable even lower prices, which expand markets further.

This is the virtuous upward spiral of free enterprise: knowledge compounding, prices falling, wealth expanding. The entrepreneur who learns fastest wins—not by hoarding but by sharing, scaling, and serving. The company that learns the fastest is usually the most profitable. Elon Musk’s companies are not just building cars or rockets—they are climbing learning curves at light speed. Musk understands that the true source of wealth is not money or matter but discovering and sharing valuable new knowledge.

Let’s go back to Grandma’s refrigerator. In 1956, you could buy a new Frigidaire for $470. Unskilled workers at the time were earning about $1.00 per hour, putting the time price at 470 hours. On July 4, 2025, you could buy one at Home Depot for $578 (the price has since increased to $628), but unskilled workers are earning closer to $17.50 an hour, putting the time price at 33 hours. For the time it took to earn the money to buy one refrigerator in 1956, you get over 14 refrigerators today. Even if they might not last as long as Grandma’s refrigerator, we’re still much better off.

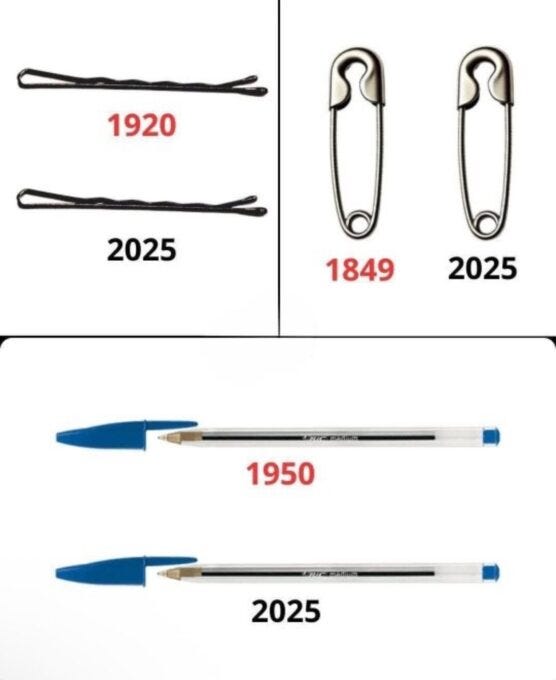

On the other hand, if a product has reached the apex of perfection, then you really do want it to last forever. Fingernail clippers may be one such example. I could be wrong, but I don’t know how to improve them. I’ve also had the same ones for 20-plus years.

Here are a few other examples:

But cars are a different story. My first car was a 1956 Chevy Bel Air. Back then, you could buy a brand-new one with the base V-8 engine for about $2,400. Even with factory options and accessories, it typically stayed under $3,000. If an unskilled worker earned $1.00 an hour, that car would cost 3,000 hours of time.

Fast-forward to 2025, and unskilled compensation is around $17.50 an hour. At that rate, the equivalent money price of the Bel Air would be about $52,500—roughly the price of a new Tesla Model Y, one of the most popular cars in the United States.

So, here’s the question: How many 1956 Chevys would I have to give you in exchange for your 2025 Tesla?

Having personally experienced both, I wouldn’t trade a single Tesla for a thousand Bel Airs. As iconic as the ’56 Chevy is, it simply doesn’t compare to what a Tesla delivers. In fact, if someone offered me a brand-new ’56 Chevy today, I’d consider it more of a liability than an asset. The Tesla far surpasses the old Chevy in every category: reliability, safety, comfort, efficiency, and especially maintenance. And nothing even comes close to the magic of Tesla’s full self-driving feature.

Some products are perfect—they work great and are extremely affordable. But most others can still be improved. We don’t want them to last forever.

Tip of the Hat: Shane McPartland

Find more of Gale’s work at his Substack, Gale Winds.

I disagree with your premise that shorter longevity contributes to innovation. Innovation should include extending the useful life. The fair evaluation of progress is the total expense, including disposal, of the items. So if an item had an equivalent cost of 100 man hours in 1960, but is now 10, but the items useful life went from 20 years to 10 years, then instead of 10x gain, it is only 5x gain. Further, I would much rather buy a new refrigerator because the new benefits are worth it to me than because my refrigerator died.

I enjoy your thinking, mostly.

Thanks Tim

Every appliance service technician I spoke to—each with decades of experience repairing machines from multiple brands—immediately blamed federal regulations for water and energy efficiency for most frustrations with modern appliances . . . The main culprit is the set of efficiency standards for water and energy use for all cooking, refrigeration, and cleaning appliances." Throw in Canada's carbon tax and a whole cornucopia of envirokook policies and I wonder why people are surprized with the cost of living increases.